Hans von Sponeck

Former UN Assistant Secretary-General & Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq

A decisive meeting for the future world order following the end of the Second World War took place in Yalta (Crimea) in February 1945. Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, a communist from the East and two capitalists from the West had come together to reassure each other and the world that they would jointly be in charge of an institution replacing its predecessor, the failed League of Nations. While the two sides differed fundamentally, both ideologically and politically, they were fully aware that they needed each other to hold the reign of power in the organisation that was about to be created. Four months later, on 26 June 1945, 50 governments came together in San Francisco to sign the UN Charter.

It took many years for the international public to become aware that the US and UK Governments had started as early as 1941 to work out, often in secrecy, a strategy for shaping the future United Nations as a westcentric institution. As it turned out, the political UN (the Security Council and the General Assembly) would be located in New York, the Judiciary UN (International Court of Justice) in The Hague, the commercial and financial bodies of the UN, the World Bank, and International Monetary Fund, in Washington. The UN Specialized Agen- cies, Funds and Programmes (as UN- DP, UNICEF, FAO, WFP, UNESCO,WHO and others), without exception, would have their headquarters either in North America or western Europe. Only recently have a few UN entities established themselves outside of the western hemisphere, for example the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in Nairobi and the UN University in Tokyo.

This reality has certainly influenced the politicisation of the work of the UN system, especially in the areas of policy, finance, and economics. Until the early part of the 21st century, the UN including its operational system, was unquestionably largely determined by western interests. Changes in the geo-political dynamics and a world order having become more and more diversified, however, have led to a trend towards dewesternization. The countries of the South which until recently, the industrialized world had condescendingly called the ‘third world’, have become much more self-confident and independent in their national decision making. Their recent voting record in the UN General Assembly (GA) is a good indicator in this respect for example with regard to the war in the Ukraine. While they generally condemned the tool of war, and more specifically, Russia’s invasion in the Ukraine in one GA resolution, they did not support sanctions against Russia in another GA resolution.

A new norm for political decision is noticeable in non-western countries. There is an awareness across the continents that the world of the 21st century is not the world of 1945 when the UN was created. As a result mo- re and more governments, and civil society organizations, recognize the need for a new international security and development architecture and the contextual urgency for liberating the United Nations from its structural shackles in order to become an ins- titution able to protect universally peace and security and bring socio- economic progress that was promised at the end of WWII. The world is still waiting.

Only a few countries have remained steadfast in their almost pre-programmed alignment with western, especially US foreign policy interests. A closer look at the debates in the GA and the corresponding casting of votes reveals a profound but not entirely surprising picture: on major issues of international concern such as disarmament and the establishment of nuclear free zones, decolonization, sustainable development, climate change, universal human rights, more equitable international trade, many western UN member states would vote against such resolutions thus preventing the development of a safer and fairer global order. The US was in the forefront of rejection. Often alone, frequently supported by only a handful of smaller nations in the Pacific like Micronesia, Palau and Nauru plus EU/NATO countries plus Canada and Israel, the US would cast consistently negative votes. The US is today the only country that has yet to adopt the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and the one western country that has yet to ratify the Con- vention for the Elimination of All Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

Non-western countries have become increasingly vocal in their rejection of such western domination. The Doha Round of Trade negotiations are the most prominent example. In 2001, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) had initiated such talks between developing and developed countries. The aim was to create a level playing field for global trade relating inter alia to agriculture, intellectual property rights and non-agricultural market access. Mainly due to US and EU refusals to reduce agricultural subsidies, these talks have failed. Developing countries remain unwilling to accept what they consider unfair trade practices.

From a non-governmental and civil society perspective reference must be made here also to the world-wide immensely destructive power of corruption in the relationships between and within developed and developing countries. Even though it has so severely impacted the lives of normal citizens everywhere, the UN has been largely helpless in containing this evil. The overall multilateral picture that is presented here is one of increasing political independence of the non-western world; the inadequate socio-economic progress of low-income countries; and the lack of political will of well-to-do countries in translating their promises into action. In 1970, as an example, the UN accepted the proposal of the Organisation for Economic Development (OECD) that .7% of the GDP of industrialized countries be made available for funding international development assistance. In 2023, only four of the 32 OECD/DAC countries (Luxemburg, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany) had met this target. The average for all countries came to a mere .37% (2022) amounting to a total of $217.7 billion or about 35% of the funds available for defence. The US was with .23% at the bottom of the scale. In contrast, NATO has established an annual benchmark of 2% of the GDP to be spent by its members on national defence. Eleven of the 30 NATO member countries have met this target in 2023. Out of a total global defence budget estimated for that year at $2.3 trillion, the US with a defence budget of $816,7 billion was by far the biggest contributor.

In summary, economically developed countries are much more ready to provide funding for their military security than for contributing their financial resources for countries trying to meet sustainable development go als for their human security .

Opportunities for genuine cooperation and teamwork in combatting mega crises such as global warming, poverty, human migration, militarisation, and impunity for violation of international law exist but are ignored, even though such crises affect all 193 UN member countries. Polarization and confrontational alliances such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organi- zation (SCO) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization ( NATO) have created deep rifts across countries and continents.

It therefore cannot surprise that non-western countries no longer want to accept western unilateralism and US exceptionalism and increas- ingly display a lack of trust in the intentions and promises of the five permanent powers of the UN Security Council which in turn contribute so decisively to the confrontational atmosphere prevailing in the UN General Assembly.

More specifically, the political UN, especially the five permanent member countries in the Security Council, has consistently failed to prevent or to solve intercountry crises. In fact, countries like the Russian Federation, the US and the UK have repeatedly displayed serious disregard for UN Charter law, most dramatically in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Yugoslavia, and Ukraine. Justifiably, public voices have started to ask whether the persistent failure of the P5 to act as a multilateral team of like-minded should lead to a withdrawal of their right of leadership the UN General Assembly has bestowed on them in accordance with the UN Charter. Its mandate as- signs to the SC “the primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security”, “to act on their behalf” and do so consistent with “the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations” (Articles 1 & 2).

The glimmer of hope for more permanent peace following the signing in 1990 of the Charter of Paris, or the Freedom Charter, as it sometimes called, by all eastern and western European countries including the USSR, and the US and Canada, waned long ago. The Cold War has continued, it only has become colder and more confrontational. Even the 1947 agreement between the United Nations and the US that was to guarantee that the US Government would ensure that the UN would be a hub where diplomats and visitors coming to New York on ‘UN business’ could come together unhindered (see UN/US Agreement of 29 June 1947, Article IV, Section 11) to discuss multilateral issues, has continuously been violated by US authorities. Permanent missions to the UN in New York from countries with which the US has either no or poor relations, often have to wait for extended periods of time before receiving diplomatic visas for their staff to join their respective missions, or they are told by the US authorities that specific individuals would not be cleared at all. Not infrequently, visas would be refused for non-governmental citizens from certain countries having been invited by the UN to come to New York to attend important UN meetings or worse, they would be cleared for their visit but only after the event was over. Just to give one example, Iraqi citizens wanting to join UN, UNICEF, UNFPA or UNDP meetings, during years of sanctions, were frequently humiliated in this way.

UN headquarters in New York has become more and more a centre of unabated geopolitical turbulence and confrontation rather than a centre where the world comes together to discuss global problems, and where compromise and convergence determine the outcome of international diplomacy.

No treaty and no law is cast into iron. Those who drafted the UN Charter understood this. For this reason they included a provision in the Charter to hold a general conference not later than in 1955 (!) to determine whether any alterations of the UN Charter of 1945 were required ( see Charter Article 109). As of today, or 69 years later, the UN General Assembly has yet to fulfil this obligation.

Aware that global pressure has been mounting for such a review, UN Secretary-General Guterres proposed last year to the UN GA to debate UN reforms at a special session of this year’s GA meeting in New York. UN member states have accepted this proposal and decided to convene on 22nd /23rd of September a ‘Summit of the Future’ with the stated objective to identify ‘multilateral solutions for a better to-morrow’. Preparations for such an important (and overdue) UN initiative are currently underway led by the Governments of Namibia and Germany as facilitators.

While the final agenda for the meeting this autumn is not yet known, it is clear that two days in September will be a most welcome beginning of what is bound to be a long and arduous reform path not in the months but in the years ahead.

The list of non-negotiable reform topics will have to include, first and foremost, the Security Council. Until 1965, the SC had eleven members, five permanent (P5) and six elected (E10). At that time, it was decided to increase the Security Council to fifteen members by adding four more elected countries. The total number of SC members has not changed ever since. While the size of the SC must be carefully considered in order to make sure that size of membership does not interfere with the efficiency of decision making. At the same time, it is also clear that the size of the SC has to be an issue since the UN GA has increased from 117 countries in 1965 to 193 in 2024. Even more im- portant is the question of the composition of the P5 and the justified demand for geographical adaptation. This undoubtedly will be the most contentious challenge for some of the current members of the Council since the composition has remained unchanged ever since the UN came into existence 79 years ago. Currently, three of the P5 countries, France, the UK, and the US, are western. Africa and Latin America are not represented at all, and Asia, with over 50% of the global population, has with China only one permanent member.

Other SC reforms that need to be considered include the use of the ve- to. Use for purely national interests has over the years often prevented the Council from taking effective action in preventing conflicts or finding peaceful solutions. Its use by the US and Russia involving the wars in the Ukraine and in Palestine are the most recent examples of misuse. Another SC reform issue has to do with the fact that the SC has never adopted formal rules of procedure, as the GA has done. The SC, in contrast to the GA, has insisted to work with provisional rules of procedure which the P5 countries find more useful in meeting their individual national rather than global interests. The prevailing stalemate in the SC to reach agreement on critical issues of international peace and security makes it necessary to consider reforms that would give the GA more decision-making authority and an ability to overrule the Security Council when the Council is unable to reach a joint conclusion. Currently, the GA has very limited authority to do so under the socalled Uniting for Peace resolution (GA RES 377 of 1950). This resolution needs to be broadened in the context of UN reforms.

Important progress has been made in recent years in integrating actions taken by the SC, the GA, and the Secretary-General involving political, peace-keeping, and human security-related executive initiatives. Reforms must be introduced to expand and institutionalize such multi-sectoral dimensions to allow civil servants from different UN departments to work together.

Valuable cooperation exists between the UN and civil society. In 2022, 6494 international, regional, and national NGOs had a consultative status with the UN Economic and So- cial Council (ECOSOC) with the right to participate in UN consultations. The reform debate must consider how such cooperation with the UN can be broadened to include similar cooperation with the SC , the GA and possibly also with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to allow Civil Society to become an integrated partner of the UN System. Such an extended role of non-state actors will most certainly be opposed by many governments as they fear what they consider undue intrusion into ‘their’ affairs.

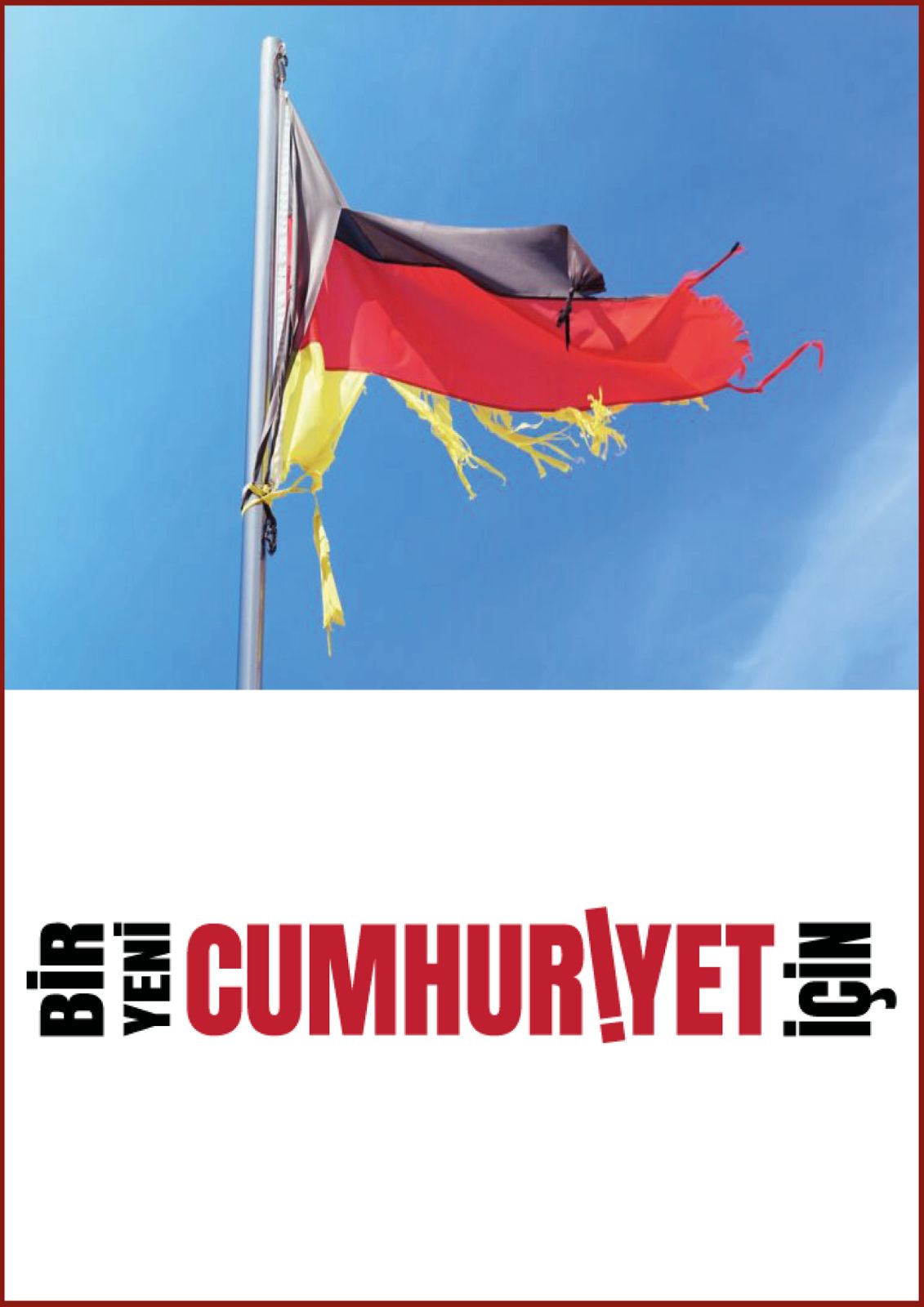

The UN reform catalogue is not only long but also very contentious. The multilateral climate at the UN headquarters in New York, as has been noted, is stormy during this time of global geopolitical confrontation and recalibration. The ‘western block’ with a population of less than 10% of the global population, must recognize that in the 21st century, multilateral westcentrism cannot have a future. Accordingly, it must become willing to join the community of nations, not as a dominator but as a member of the UN global order team.

It remains to be seen whether the UN reform debate will also include consideration of shifting UN headquarters from New York to another location where the overall atmosphere for multilateralism maybe less contemptuous. This issue is not new. It has been raised before. Such a UN location debate could evolve around three options: option i: if there is a convincing assurance by the ‘West’ that it is ready to accept democratic principles in multilateralism and become a reliable UN team member, in the short run, admittedly most unlikely, the UN could conveniently remain based in New York. Option ii: UN HQ moves to either Geneva or Vienna, two locations where basic UN institutional infrastructure already exists. This, of course, would mean that the UN HQ remained located in the western hemisphere. Option iii: The UN finds a new location else where. There are locations around the world of 8 billion+ people with hopes for a better tomorrow and an inter- national organisation that is reliably peace-minded, with powers, big and small, working together, where international law is respected, and accountability rather than impunity prevails, and human dignity for all and respect for nature exist.

Yes, words, meaningful words but little more than words – a daydream and a nightmare. Where to find such a place where the seeds for this better tomorrow can find good soil? A theo- retical answer: There are places, e.g., the capitals of Bhutan (Thimphu), Costa Rica (San José), Botswana (Gab- orone), Oman (Muscat) – all peaceful UN member countries but regrettably not suitable to receive an organisa- tion representing the interests of 193 member states. But there is Singa- pore, a stable and sprawling city with 5.9 million people, a third of the size of New York City with its 20.1 million inhabitants, and a seasoned UN mem- ber state since 1965. It could do bet- ter on human rights and on climate change policy, but it has a crime rate that is among the lowest in the world, and according to Transparency Inter- national (TI) after Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, and Norway comes Sin- gapore as the country with the fifth lowest corruption rate.

aWhat about it?