Dear participants, dear guests,

I would like to welcome you all to this conference which is organized by SADTU and PoliTeknik. Thank you for accepting our invitation. We are very grateful and honored that you are participating today in the symposium of Project Extension of Human Rights to Education, in short Project Article 26.

We feel honored that the Honorable Minister accepted our invitation. We are all very pleased that honorable Ms Minister has spared us her valuable time on this wonderful day to deliver the opening speech of this symposium. We express our sincere gratitude.

This meeting was possible to organize thanks to the dedicated efforts of SADTU and the contribution of NACOSA. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the entire SADTU team, in particular to esteemed Comrade GS Mugwena Maluleke, and to NACOSA for this. We were in constant contact with Comrades Renny Somnat and Cindy De Lange during the preparations for the conference and I would like to mention their names here and thank them.

Dear participants, dear guests,

My knowledge of English is limited, so I would like to inform you in advance that I will have some challenges with articulations. I prepared my presentation in Turkish and translated it into English with the support of an interpreter. Please excuse me in advance.

After the symposiums we organized in Germany in 2016 and 2018, today we come together for our 3rd conference. We are in Africa for the first time and we are in the right place, because half of our partners from 48 countries come from the African continent. Why do we have so many partners in Africa? Well, I am trying to make sense of this myself, and maybe the title of this symposium might give an answer.

In my presentation, I will first cover the origins of the project, I will share some important impressions and memories, and examine the geopolitical climate in which the project was implemented, and I will reveal its objectives, its organizational strategy, its successes and challenges. By doing so, step by step, I will summarize the past 7 years in an outlined manner. At the end of my presentation I will give a few minutes to my colleague Prof. Michael Winkler from Germany. We’ve been working with him on this project for many years (Prof. Marliese W. Fröse took the floor instead of Prof. Winkler during the conference).

Dear participants, dear guests,

Project Article 26 was first discussed as an idea in PoliTeknik magazine in autumn 2015. It was developed in a series of articles published in the journal under the title Ideas and Recommendations on the Extension of the Right to Education. The project further evolved at the October 2016 symposium and was officially started in January 2017. From conception to preparations, from implementation to experiences, the process took 8 years. In a sense, it was a very long struggle for survival for a movement that started from the ground up, on a voluntary basis, without any national or international support, without any connections at the beginning, with personal dedication and pure human power. It is good that we have continued so that we can be here today with our colleagues and comrades.

Our first contact with SADTU dates back to 12 October 2015; we wrote an email asking for their contribution to the series of articles, and a week later we received a positive response. Since then we have been in contact.

I am quoting from an email I wrote on 27 October 2015 to Prof. Michael Winkler, with whom I am working on this project (translation from German):

I am quoting from an email I wrote on 27 October 2015 to Prof. Michael Winkler, with whom I am working on this project (translation from German):

“[…]„The published series of articles represents the first step in the preparations for a conference on the same topic next year. The event is intended to implement a two-year project (until 10 December 2018; 70th anniversary of the UN Declaration of Human Rights), which envisages the establishment of a coordination office and a scientific council. These are to organise cooperation at a global level with all stakeholders seeking to expand the human right to education, develop their joint positions and inspire the global public and UN member states to implement these positions.

In the coming weeks, PoliTeknik plans to approach potential partners for project development and long-term cooperation as part of this commitment and to win them over for this commitment […] ”.

The mere preparations, infrastructure and introduction of this initiative, which was planned for two years, now seems to easily exceed 10 years. Given the time that the UN, with its vast resources, has spent on the Millennium Goals and Agenda 2030, more than 2 decades as of now, 10 years is really not that long.

Dear participants, colleges and

comrades, what Project Article

26 aspires to achieve?

The project will be based on a foundation of international legitimacy for the redrafting of Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Several social actors involved in the extension of human rights to education will work on different aspects of this issue in order to create a “Declaration on the Extension of Human Rights to Education” to be voted at the UN General Assembly. The project focuses on Article 26 of the UDHR, which needs to be amended in a phased extension.

Article 26 of UDHR:

1.

Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

2.

Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

3.

Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

Dear participants, dear guests,

The goal of extension Article 26 of the UDHR while developing a broad base of legitimacy will be a meaningful experience for all people excluded from democratic decision making processes. This is an interesting relevant perspective, a vision, because there is rarely time for humanity to act as legislators and articulate it’s from the outside undistorted interests. We have formulated these words as a motto: The sections of humanity excluded from democracy will experience themselves as a legislator and a representative of their interests that are not distorted from the outside.

The uniqueness of our initiative lies in its refusal of concepts prepared by elites or circles that produce the illusion of broad participation. In other words, the project does not seek support for a ready-made concept, nor does it relegate participants to a passive, subordinate position. Instead, all partners in this initiative are invited to work actively and design the content of the declaration themselves. The project is designed in such a way that it cannot function without the active participation of volunteers. The idea therefore rightly sends the following message: Please build your own unity together!

This project should be organized in the same way a country drafts a constitution: imagine a constitutional process that invites all social groups to participate. Take the example of Cuba’s constitutional draft, which was adopted on February 24, 2019 with a vote of 86% in favor. „Out of a total island population of 11 million, 7,370,000 people participated in the constitutional debates. 111,872 discussion meetings were held. During these meetings, 1 million 445 speeches were given. There were 659 thousand suggestions, 560 thousand requests for amendments, 27 thousand requests for additions and 38 thousand requests for deletions”1

Dear participants, dear colleagues and comrades,

How many of us are ready for such an endeavor, how many months or years do you think patience and concentration can last? If this project is a worthy effort, it will certainly not be easy. It is clear that we are not wasting time on small reforms.

Such a strategic approach entails the exclusion of imported agendas, and requires maturity and emancipation. We can characterize this as the first step towards self-determination trough self-awareness.

We, the initiators of the project, have therefore intentionally limited our task to coordination and handed over the determination of the content to experts and to those who make democratic demands. And the coordination activities have been opened to all partners through the commissions that we have established and which will be presented tomorrow. This will make it possible to bring together progress that is probably stalled at the national level through our project at the international level. The concrete goal of extending Article 26 allows us to interact permanently, in real-time and plan joint activities globally.

We, the initiators of the project, have therefore intentionally limited our task to coordination and handed over the determination of the content to experts and to those who make democratic demands. And the coordination activities have been opened to all partners through the commissions that we have established and which will be presented tomorrow. This will make it possible to bring together progress that is probably stalled at the national level through our project at the international level. The concrete goal of extending Article 26 allows us to interact permanently, in real-time and plan joint activities globally.

I will now present some of the highlights from the article series „Ideas and Recommendations on the Extension of the Right to Education“ and from past symposium speeches, because they contain the first opinions which set out the need for the project and guided its discussions and showed a direction for the critical perspective in this debate.

At perhaps no other time since the right to education was enshrined in the 1948 United Nations declaration of Human Rights has it needed a renewed pledge in light of today’s increasingly complex global reality. Although great strides have been made to increase access to education during the last 15 years, 60 million children remain out of school. In spite of education being an inalienable human right and a public good, across the world this right continues to be denied due to a combination of under-financing of education, the impacts of inequalities in accessing and completing education and above all, a lack of political commitment and will.2

Susan Hopgood

President of Education International

Federal Secretary of the Australian F Education Union – (AEU)

Today, human rights and the right to education are attacked on a daily basis worldwide. Despite the gains that have been made, our collective human and civil rights work is far from complete. The UDHR’s education declaration must be refreshed and modernized to establish more ambitious and specific goals, with specific reference to the rights of girls to education, as well as the rights of all children to early childhood education and secondary education.3

Mary Cathryn Ricker

Executive Vice President of the American

Federation of Teachers (AFT) – USA

We find ourselves in an era of vastly expanding advancements in all facets of life. Technology, Medicine, Agriculture, Engineering and the Arts are all progressing quickly but many developing countries are being left behind due to the lasting effects of colonialism, global capitalist economies which dictate a narrative of oppression and political systems which are designed to exclude the voice of the masses. The only way to remedy this is by educating our people and providing them with specialised skills to fulfil their personal potential and to contribute to reaching the potential of the country.

It is therefore necessary for the rights in Article 26 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights to include further education and training in an attempt to address the issues outlined above.4

Student Representative Council

Wits University – South Africa

Human rights education and the right to education are interrelated, because the UDHR must be read by everyone, understood in terms of content and interpreted in the respective social and historical context.5

Prof. Dr. Eva Borst (Germany)

would like to start with a quote: “Equal exploitation of labour power is the first human right of capital.” This is how Karl Marx put it in his Critique of Political Economy of 1867 (MEW 23, p. 309). In analogy to the topic of our conference, one can continue Marx’s ironic sentence with the formulation of another human right, for example as follows: “General production of labour power (thus education) is the second human right of capital.” Educational understanding and practice are subject to the constraints of social production and reproduction and the relations of domination that correspond to them. Domination and the government assigned to it determine the hegemonic understanding of education, what is to be understood by education. They define what education is and determine the scope, quality and tailoring of educational services from their concrete interests.6

Prof. Dr. Armin Bernhard (Germany)

Lindgren Alves (2013, p. 24) draws attention to the Western character of the UDHR, highlighting its Enlightenment heritage, like that of the UN itself. The author states the following:

Adopted in this way, without consensus, in a forum then composed of only 56 States, Western or “Westernized”, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was not, therefore, “universal” even for those who participated in its creation. Under these conditions, those who did not participate – the vast majority of today’s independent States – had more reason to label the document as a “product of the West”. (Alves, 2013, p. 24, free translation).7

Prof. Reaquel Melo (Brasil)

These are indeed interesting positions. Some call for a modification of Article 26, others believe that a real democratization of the education systems is in fact a head-on collision with the existing world order. These indicate that the fundamental debate before the declaration needs to go much deeper. We have already targeted the following issues: Questions can be discussed as to whether the project, with the aim of progressive modifying Article 26, is only meant to send a signal, and can it do so at all? Can we get a vote at the UN General Assembly? What happens if our joint declaration is rejected? How should we then proceed with a strong, globally established legitimacy base? Should the vote be positive, would this result already be seen as a guarantee for the realization of progressive change in the countries? Should the declaration formulate a concrete control mechanism to ensure implementation? In the case of a positive or negative vote, is the UN in its existing form the right address?

Inspired by these questions, I would like to give you an example. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) was founded in 2007. Its goal is explained as follows:

“On July 2017 – following a decade of advocary by ICAN and its partners – an overwhelming majority of the world’s nations adopted landmark global agreement to ban nuclear weapons, known officially as the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. It entered into force on 22 January 2021“8

The first two paragraphs of Article 17 of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons are as follows:

1. This Treaty shall be of unlimited duration.

2. Each State Party shall, in exercising its national sovereignty, have the right to withdraw from this Treaty if it decides that extraordinary events related to the subject matter of the Treaty have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country. It shall give notice of such withdrawal to the Depositary. Such notice shall include a statement of the extraordinary events that it regards as having jeopardized its supreme interests9

As you can see, an NGO can convince the UN General Assembly, but the crucial question remains between the adoption of demands and their implementation. Let’s imagine that we expand the right to education through a declaration, would it be acceptable that states can restrict this right in special cases? In the declaration we want to draft, these aspects have to be taken into account.

Other fundamental questions also need to be asked: Can human rights be definitively formulated? Do we have to take the biological nature of human beings or the social characteristics of the societies they founded as a starting point or a combination of both? Whose interest and what image of humanity underlies the UDHR? Is an evolutionary process underway that determines the socio-historical context and has to be re-evaluated from one age to the next? If so, what kind of extension is imminent in our age?

Dear participants, colleagues and comrades,

I would like to continue as follows. Does talking about extending human rights to education mean taking courage against the global downward trend in education?

“From the end of the last decade, along with Greece’s unbearable financial debt, basic human rights are also up for negotiation, among which is the right to education. Under such conditions, the goal of collective struggles can easily be shifted from the extension of social gains to their defence, with any dialogue on further extension seeming an undue luxury“.10

Dialogue on extension of rights as an undue luxury? Well. For once in our lives, we wanted to allow ourselves that kind of undue luxury with the Project Article 26!

It is very difficult to get free of the images of the old world and imagine a good future. Dreams are subject to auto-censorship. When it comes to the extension of democratic rights, we are pessimistic enough to call it a luxury. These heavy chains of thinking clearly define the size of the existing oppression that needs to be overcome.

Dear participants, dear guests,

I would like to share with you a short but very important memory, which we have often mentioned in many of our talks. When we came up with an idea for extension article 26 of the UDHR in 2015, we shared it with our close circle; and one of our friends, Cem Şentürk, he is still working in the Foundation Centre for Turkey Studies and Integration Research in Germany, said the following; “Yes, this article can be amended, but only after a great war!” Of course, by referring to the Second World War.

And now this question is confronting us all: Will a truly great war be determinant? And what about the events after 1945, colonialism, the neocolonialism articulated by Kwame Nkrumah, the Cold War, coups, civil wars, revolutions and counter-revolutions, unipolar or rules-based international order, debates about a multipolar order… what is the answer? Are we facing a sufficiently painful collapse of civilization in the new century? The destruction of civilian settlements in other countries is not enough for us to be buried under the rubble of lawlessness? It is a question that everyone is obliged to answer. We have returned to the conditions of the World War I and are witnessing the division of the world capitalist market between the rising superpowers and the old ones. After the World War I, the League of Nations was established, its aim was to keep the peace, it was not enough, the World War II gave birth to the UN, it was not enough.

This is a time when the war supporters now pride themselves on having successfully misused agreements under international law into war tricks and how brilliant they understood the teachings of the famous Chinese military theorist Sun Tsu. In the face of this, there’s no place for us anymore for hesitation. Yes, this is a perfectly legitimate question: After or before a great war? In past conversations and debates we have tried to answer this question in the following way:

“Anything can come to an end anytime, and everyone or everything may have to start and set out it again from our current point. Humanity, in any case, will live and learn whether it adopt human rights permanently, after or before a big disaster, through a conscious activity based on its free will.

In this essential time-course, we prefer to leave audience grandstand; and this move indicates a tremendously dynamic situation: We have no doubt that in this project, there is a quality of life which emerges thanks to an engagement occurred in an optimist manner and in harmony with social nature of human“.

Dear participants,

colleagues and comrades,

Up to this point in my speech, my focus has been on pointing out the reasons for our demand for the extension of Article 26 of the UDHR and the historical turning point when it is taking place. This is a time of growing recognition that the balance of power, laws, images, aesthetics and all other elements of the old world are rapidly collapsing. The new is being born with all of its pains and waiting to be characterized. And we seek to define the educational dimension of the new world. Yes, we “dared” to do this together with those who are excluded from democracy. Do these words, dear participants, colleagues and comrades, sound a bit pompous words? At this point, let us ask the question: If we were billionaire philanthropists, would we need to talk about courage? Circles of interest that can go so far as to authorize the WHO to intervene in the internal affairs of states over epidemics can easily engage in the most undemocratic practices when they wish. No, our request is in no way from the sphere of fiction, it is nothing else as the recognition of the right of the masses to envision the future also for themselves.

I will now explain what kind of strategies our project follows and what phases it foresees.

Our 2 phases and awaiting duties

In general terms, our project is moving to a turning point of ground breaking works. These ground breaking works will be considered complete once a certain number of countries have joined the project. In other words, when the participants of the project will have a common view regarding sufficient legitimacy of the upcoming declaration, the ground breaking works will be regarded as completed.

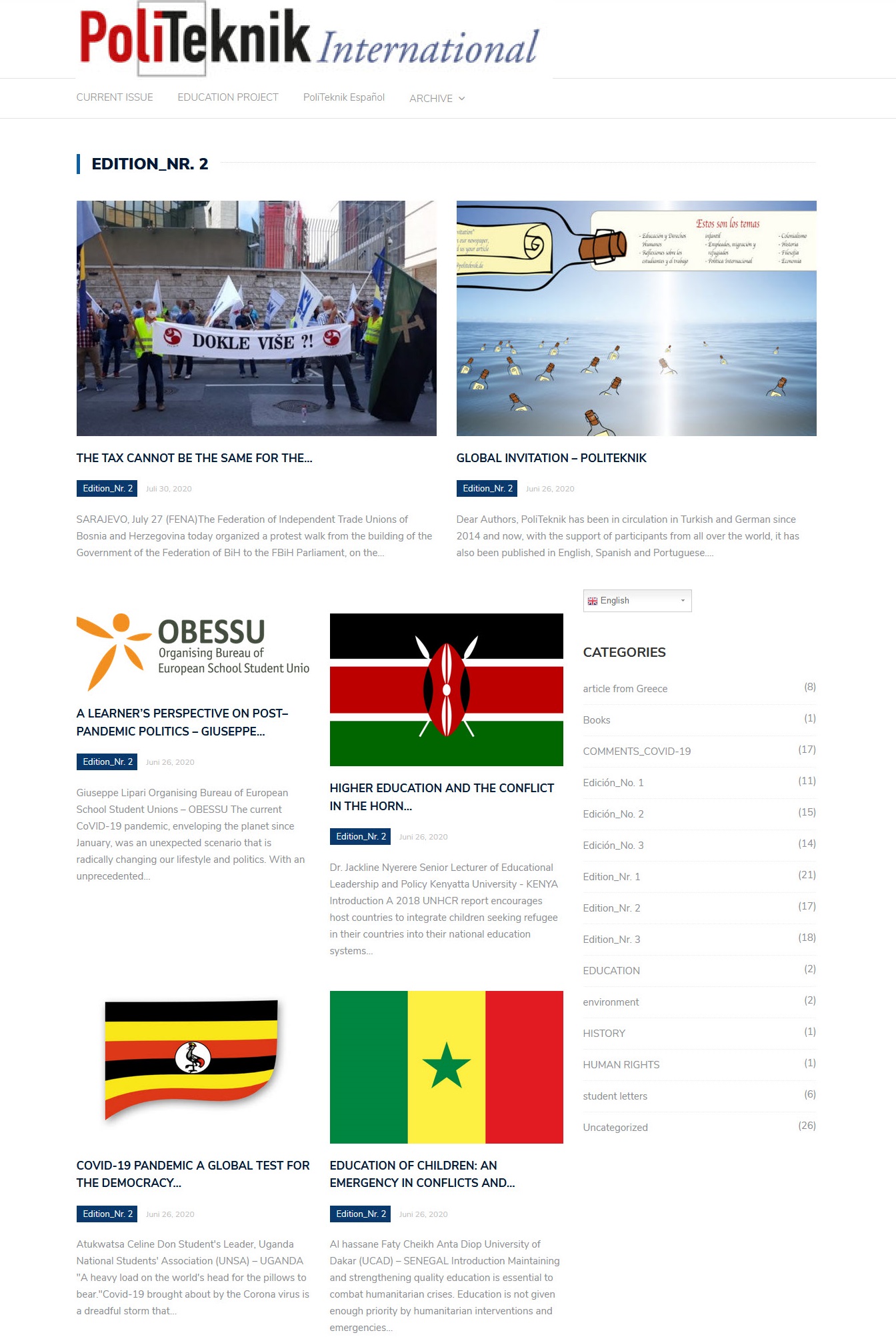

In this first phase of the project, the partners support to extend the number of partnerships to many other protagonists in different countries. For this goal, our project dossier has already been translated into 8 languages: English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Portuguese, Russian, German and Turkish.

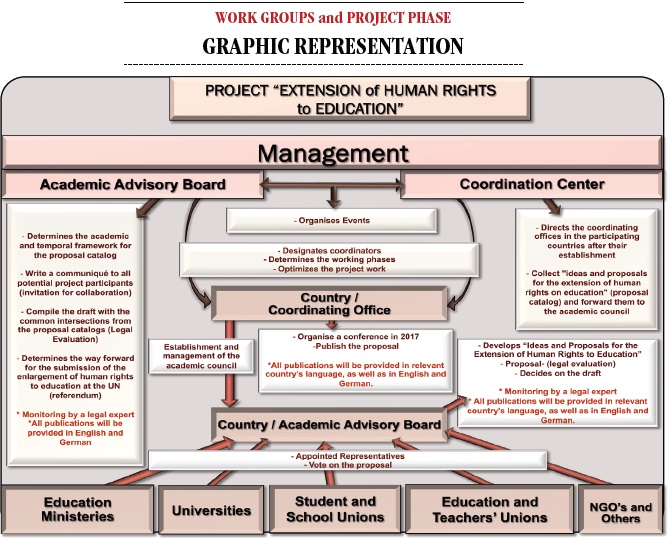

Once legitimacy has been established and coordination units have been set up in countries, academic advisory boards can be established. The academic advisory boards will prepare catalogs of proposals for the joint declaration. This first phase of establishing legitimacy is still in progress.

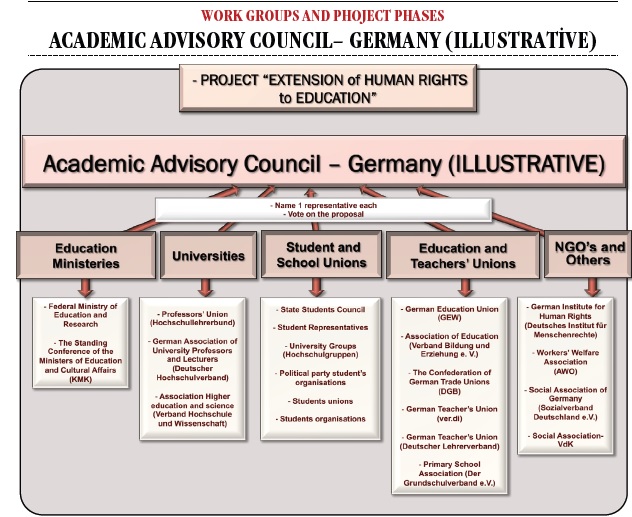

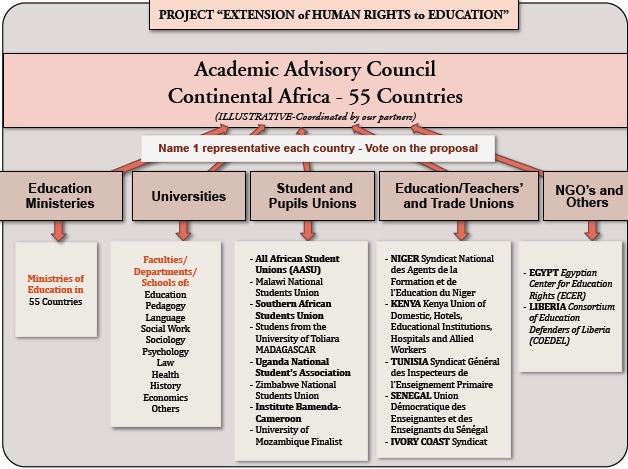

The following tables visualise our planned structures at local, continental and global scales.

TABLE 1

TABLE 2

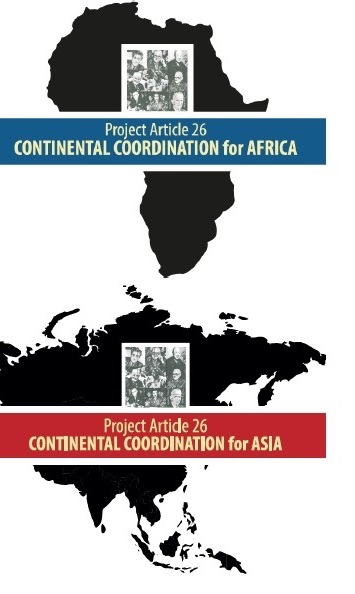

As of July 2021, continental coordinations are also considered as active organisations for the project. Logos of continental coordinations:

As of 5 May 2023, we started to establish three commissions.

1) Commission for the development of relations with UN bodies and governments

2) Commission for the development of relations with trade unions, federations, universities, NGOs, students and student unions, parent organisations and experts

3) Commission of experts for analyses and publications on current global education policies and debates.

These three methods that we have followed to develop our international legitimacy ground have been activated in recent years. In particular, the United Nations, the Education International (EI), the World Federation of Teachers’ Unions (WFTU-FISE), IndustriALL, the Building and Woodworkers’ International (BWI), etc., which operate on a global scale.

Table 3: Example of continental coordination in Africa

TABL§ 3

On 10 December 2018, we sent a letter to the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres requesting a meeting. We had a meeting with Robert Skinner, Director of the UN Partnerships Bureau, on 10 July 2019 on behalf of the Secretary-General. In this meeting, we requested that our project dossier be forwarded to the representatives of all UN member states. We did not receive a positive response to this request, as it was stated that the countries were busy with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Education International (EI) is a federation of education unions and organisations from nearly 180 countries. The chronology of our continuous efforts to develop cooperation with EI since 2016 is as follows:

• 2016: E-I was represented by the President of the German education union GEW at our international symposium in Cologne. E-I was of the opinion that the UDHR should not be put up for discussion and recommended not to take up the project. We decided to continue and the project started officially on January 2017.

• 2018: following recommendation from colleagues in India, an official invitation for partnership was addressed to the E-I President Mrs. Susan Hopgood. Our colleague Mr. Rampal Singh (may he rest in peace, we lost him this year), who was an E-I Board member at the time, handed over this invitation at the E-I board meeting in Brussels

• July 2019: Another invitation was handed over to the GS Mr David Edwards during the E-I World Congress in Bangkok. Colleagues from the Turkish, Nepalese, Somalian and other teachers’ unions handed over this letter

• November 2019: : Colleagues from the Turkish and Spanish teachers’ unions agreed with us to talk to David Edwards in Brussels about the project partnership.

• Decenber 2019: After our colleague Heleno Araujo, President of the CNTE-Brazil, shared David Edwards’ contact details with me, I sent to him the invitation again via WhatsApp.

• Between 2020 and 2021 we repeatedly tried to contact the EI continental representative offices. Finally, in December 2022, another invitation was delivered to David Edward in Cambodia by our partners from India and Sri Lanka. Since 2016, there has been no response to any of our attempts, neither verbally nor in writing.

A similar situation happened with the World Federation of Teachers’ Unions (WFTU-FISE). I communicated to WFTU-FISE President Mohanty from India and Second President Jayasinghe from Sri Lanka that I would present our correspondence in the form of constructive criticism at this conference. In an email I sent on 22 August 2022, I stated the following:

“As you know, as PoliTeknik magazine, we have been trying to invite WFTU and FISE to become partners in our project ” Extending the Human Right to Education.

Unfortunately we have not made any progress for nearly 3 years. It is shocking that comrades from the WFTU or FISA ignore us and our efforts to establish contact!

[…]The answer we received by e-mail on 05.10.2020 is as follows:

“FISE supports the campaign “Extending the Human Right to Education in the UN Declaration of Human Rights” and the amendment of Article 26 of the Declaration of Human Rights. For the fulfilment of every child’s right to education to become a reality in the 21st century. We will send our official document next week“ […]

We underlined the importance of relations with International Education Federations. Teaching is an idealistic profession that contributes to the growth of small potentials. However, we were surprised by what we encountered. Therefore, we decided to educate ourselves.

Over the years, through PoliTeknik relations and especially through our online research, we have collected the contact details of approximately 17,000 experts, trade unions, student unions, NGOs, etc. and informed them about our project. We illustrated this hard work with the metaphor of a letter in a bottle. As you know, sailors used to put their letters in a bottle and leave them in the seas and oceans, with the dream that maybe one day they would reach land and someone would read them. It is known that some letters were washed ashore after a century. We now have more than 100 volunteers from about 50 countries who read the letters in our bottle and responded positively. The first phase made progress under these conditions.

Dear participants, dear guests,

The goal of extension Article 26 of the UDHR while developing a broad base of legitimacy will be a meaningful experience for all people excluded from democratic decision making processes. This is an interesting relevant perspective, a vision, because there is rarely time for humanity to act as legislators and articulate it’s from the outside undistorted interests.

Second Phase

The second phase, which has partially begun, will constitute a platform for a long-term and in-depth debate. A platform on which the Declaration will be based on the legitimacy created.

In this second stage, a campaign of clarification is needed. On the one hand while seeking answers to a series of questions we have mentioned above, what is a human being, are human rights universal, can they be formulated in an ultimate way, should they be modified according to the historical period, etc., on the other hand, the formulations of those who make democratic demands in this direction should be brought to light. As in our series of articles.

The expert commission that we have set up should put the crucial aspects of the discussions into a general framework, and the democratic demands should be placed within this framework and gradually developed into a declaration. The expert commission members are:

• Prof. Dr. Michael Winkler

• PoliTeknik (Represented by Zeynel Korkmaz)

• Prof. Dr. Vernor Muñoz Villalobos (Former UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Education)

• Interdisciplinary Research Center for Children, Society at the University of Wuppertal (Represented by Prof. Dr. Heinz Sünker)

• Prof. Dr. Armin Bernhard

• Prof. Dr. Marlies W. Fröse

• Prof. Dr. Eric Mührel

• Prof. Dr. Karin Lauermann (Federal Institute for Social Pedagogy – Austria)

• Rama Kant Rai (National Coalition for Education – India)

• Dr. Benjamin Bunk

The framework parameters are guidelines for the preparation of the proposal catalogues in the respective countries. They aim to regulate a complex text production process for the purpose of formulating a common declaration by clearly defining areas of responsibility.

The scientific advisory board specifies the areas of responsibility for the creation of the proposal catalogues. Here is an example of a framework:

All proposal catalogues take a position/comment on:

a) Definition of education

b) Quality of education

c) Costs of and access to education

d) Providers of education

e) Duration of education

f) Implementation of the declaration

g) Others (max. 10 pages)

A maximum of 5 articles may be written for each point. The justifications for these articles will be made available to the coordination management and will be published or archived.

The proposals are written in the form of legal articles, each of which can consist of a maximum of 200 words. All catalogues are entered into the form provided for this purpose (WORD file; font: Arial; point: 12). These are written in the tradition of the UDHR in a language understandable to the masses.

Naturally, we are also carrying out activities to deepen the discussions required by the second phase. In addition to articles and symposia, in February 2022 we organised a series of online presentations in different languages, for example under the following headings:

• Project Article 26 andthe role of UN: What to expect?

• Human Rights and Discourses: Is an Ultimate Definition Possible?

• Following the footsteps of humanity

• Textile unions and the right to education

• Human right to education and the world of work

• The erosion of the International Law

Working Plan for 2024

• Academic Advisory Board will meet in February to finalise the Framework parameters

• An interim report to be drafted for submission to the UN Secretary- General in May

• The committees will continue to develop the legitimacy base and will hold meetings to visit both the UN and ministries of education in different countries

• Online presentations and publications on Article 26 will continue

• Textualisation of first proposal catalogues for the extension of human right to education

• Publication of the second project book

Dear participants,

Dear colleagues and comrades,

The progress and success of the project can be measured by the level of commitament of the partners. It stagnates or increases exponentially with the performance of those involved. And the possibilities of so many partner organizations must be well understood, these are in fact immense. We are just waiting for it to finally unfold. We cannot repeat this fact often enough.

EPILOGUE

The Project Article 26,

• is an initiative of those who are excluded from democracy,

• stands for the recovery of realistic hope,

• means the rediscovery of solidarity,

• stands for the critique of the existing concept of humans (in their absolute majority) as degraded beings.

Frequently repeated slogans of

the project are:

• This project is a longterm process. Sooner or later an exponential rising will be a natural result of its’ continuous engagement

• Project Extension Of Human Rights To Education – is a special democratic experience for humankind

• Those parts of humanity excluded from democracy will experience themselves as a legislator and a representative of their interests that

have not been distorted from the outside.

• Extending Article 26 of the UDHR before or after a great war? In this determinist time-course, we prefer to leave audience grandstand; and this move indicates a tremendously dynamic situation: We have no doubt that in this project, there is a quality of life which emerges thanks to an engagement occurred in an optimist manner and in harmony with social nature of human.

Thank you for listening to

my presentation,

Zeynel Korkmaz

PoliTeknik

- https://www.kubadostluk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/KAY-A4.pdf, Page 7; translation: PoliTeknik. ↩

- English Project Dossier: https://politeknik.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/PROJECT_DOSSIE_EN.pdf, Page 6. ↩

- ibidem: Page 6. ↩

- ibidem: Page 7. ↩

- Thoughts and Recommendations on Extending Education Rights in UN Declaration of Human Right: https://politeknik.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/DOSSIER-BILDUNG. pdf, Page 19; translation: PoliTeknik. ↩

- Armin Bernhard, in: Extension of Human Rights to Education: https://politeknik.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Extension-of-human-rights-to-education.pdf, Page 165; translation: PoliTeknik. ↩

- The Project “Extension of the Human Right to Education” and the role of the United Nations Organization: limitations and possibilities – https://politeknik-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/PoTe-INT_6.pdf, Page 10, 11; translation: PoliTeknik ↩

- https://www.icanw.org/the_treaty; translation: PoliTeknik ↩

- TREATY ON THE PROHIBITION OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/tectodevms/pages/2417/attachments/original/1571248124/TPNW-English1.pdf?1571248124, Page 10; translation: PoliTeknik ↩

- https://politeknik.de/p13186/; translation:

PoliTeknik ↩