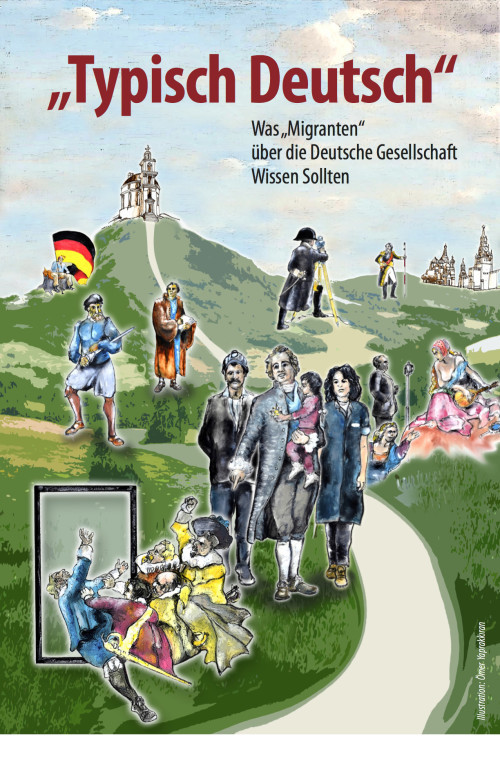

“The Germans, in other words, are passionate planners – but they often become victimes of their own over-planning. Things don’t go wrong, as they do in Britain, because of laziness or because a railway safety officer has overslept. Things go wrong in Germany because people refuse to believe their planning could possibly be wrong.”

Ach, Herr Boyes…How many times have I had a conversation with a German diplomat or Beamte from the Bundespresseamt that begins with this long long sigh…ach, Herr Boyes. It is the prelude to a short speech about the failure of the British press to understand the nuances of German society. And it is almost always about the Second World War. Next year is the 100th anniversary of the First World War so maybe the English will use a different historical period to be rude or teasing about the Germans.

But for the time being we are frozen in the Sceond World War. Every football match between our countries prompts headlines from the English Boulevardpress along the lines of “Blitzkrieg! Germans storm towards the English goal!”. I have to agree with the Beamten from the Bundespressamt on this: the references to a war which none of us can remember are not very funny. Somehow though British attitudes are still being shaped by the war. Most generations–not just those,like me, who were brought up in the 1950s when war memories were still fresh–have watched at least two war films: the Guns of Navarone and Escape to Victory. The first is a straightforward adventure story, the attempt by a group of soldiers , led by the actor Gregory Peck, to take over a German fort on a Greek island. The second film is about an attempt by prisoners of war to escape under the guise of a football match from German imprisonment. The film features Sylvester Stallone and the former England soccer captain Bobby Moore who play a unscupulous Third Reich team of blond thugs and Nazis. Both works are rubbish and are shown again and again on British television being regarded, for some reason as perfect Christmas viewing.

They are important though for the way they depict the Germans. There are of course some predictably evil Nazis, there is at least one kindly German but most of the Germans are simply stupid, easily fooled. This has always baffled me. Why should a nation that has produced so many Nobel prize winners, so many famous chemists, engineers and mathemeticians be presented as numbskulls as soon as they put on a uniform?

The answer is this: after 1945, Britain which had won the war, lost its Empire. Germany which had lost the war, had a Wirtschaftswunder, an economic miracle. The memory of the war, the horror of the Holocaust, got wrapped up in our minds with the unfairness of the situation. How could the losers become winners? West German factories, which we had bombed, re-equipped themselves with modern technology, partly bought with the help of Marshall Aid. British managers helped re-construct Volkswagen in Wolfsburg and the new free press in Hamburg. Afraid of how the Russians might exploit an impoverished West Germany we helped build up again what we had destroyed a few years earlier.

The result: while the English were still living on rationed food ten years after the war, West Germans often had enough cash in their pockets to take a foreign holiday. By the 1960s, as package tourism started up, British and German workers were competing for beds in the same Spanish hotels, and for the same sunloungers around the swimming pool. The Germans had more cash than the English, often got better treatment from the Spanish waiters and had the irritating habit of getting up shortly after dawn to lay their towels on the sunloungers, booking them for the whole day. By the time the British tourist had woken up, usually with a sangria hangover, had breakfast and stumbled to the pool he was confronted with occupied German territory.

There was a simple explanation for this – the Germans were more disciplined than the British. But we were unwilling to accept such an unflattering conclusion. So we started to construct theories about the Germans. They were, we decided, obsessive planners. They divided up their days, stuck rigidly to a routine. Summer holidays were booked in November –still unthinkable for most Englaender– the same month that Christmas presents are bought and neatly parcelled. And when schoolholidays began in Germany, the proud Familienvater would pack up his car on the night before the great exodus to the south. Alarms would be set for four o clock, the whole family prepared –with, yes, military efficiency– for an early start from Bochum to the Brenner Pass. The first day of holidays is Autobahn-Hell. But rather than, for example, starting a day later or taking the children out of school a day earlier, the German family presses ahead. The local traffic radio is switched on to alert Familie Mueller to the latest Stau. Naturally as soon as the radio recommends an alternative route all listeners take it – and another Stau is created.

The Germans, in other words, are passionate planners – but they often become victimes of their own over-planning. Things don’t go wrong, as they do in Britain, because of laziness or because a railway safety officer has overslept. Things go wrong in Germany because people refuse to believe their planning could possibly be wrong. The rest of the world was astonished that the Berlin-Brandenburg airport could become such a chaotic project, endlessly delayed. But we weren’t at all surprised in Britain. We know that this is ,in a certain way, Typisch Deutsch. And we know –please forgive me Bundespresseamt– that this is how the Germans lost the war. Not because their soldiers were worse than ours but because all but a handful of generals (Rommel is a big favourite of the British) were reluctant to change their plans even when the tide of war was shifting.

That, and only that, has made us feel better about ourselves. We like to think of ourselves as gifted amateurs, people who prefer to improvise. The Germans–that is our stereotype at least–are nervous of taking untested risks, prefer clear command structures and want to know what they are going to eat for dinner tomorrow. They are the most insured society in the world. The British think insurers are cheats and avoid them whenever possible.

That’s why these post-war films show Germans as slow-thinkers. It is unfair but the Germans should not take offence. German Ordnung, mocked by us, preserves some valuable social assets that we in Britain have been neglecting. For example: Germans still take the division of work and free time very seriously. In London, office and private lives merge into one–nine, ten hours in the office, followed by drinks with colleagues and then an hour’s commute home. Most Londoners find their future partners at work. But Germans ,by making a clear separation, work and play more efficiently. As a result, Germans also take friendship very seriously. In London it is possible to go several months without seeing ones best friend even though you live in the same city.

In economic terms, our initial resentment of German success has turned into admiration. Germany managed to avoid some of the worst of the financial crisis by staying true to the stereotypes. One of the British problems was the hedge fund managers who moved into traditional companies and stripped them down to their few profitable components. Germans though always planned ahead, resented short-termism and developed long term strategic investment plans. That’s why Germany has a thriving car industy while Britain no longer has one. And it is why Germany does well in China where you can never get a quick profit. The Germans have patience in their bones, in their DNA.

Margaret Thatcher was always convinced that Helmut Kohl had a secret plan for Europe, imagined that it was written on a piece of paper somewhere and instructed her diplomats to get hold of it. It was correct of course that the two leaders did not like each other. But Thatcher had a kind of admiration for Kohl’s stubbornness. Thatcher was amazed and a bit upset when the German chancellor abruptly interrupted difficult talks on the Wolfgangsee and left the room. Later she spotted him in a Konditorei tucking into two Schwarzwaelderkirschtorten with huge dollops of Schlagsahne. “He’s soooooo German!” she told her aides. She didn’t mean the cake, or the rudeness–she meant Kohl’s respect for routine, his orderliness. He always had cake at four o clock and not even fierce talks with the British leader about the future of Europe was going to break his rhythm.