It has been widely accepted that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 was a catalyst for the independence of African and Asian European colonies. Human Rights are rights that everyone has in virtue one being human. This includes the right to be respected and fulfillment of civil and political liberties as well as social and economic needs. Human Rights Principles are seen to be one of the driving forces behind the wave of decolonization and the push for independence after 1945 and since the beginning of the Cold War. Here, we must not ignore the roles played by countries who gained independence early during this period (early post-colonial countries such as India and Pakistan) in shaping the human rights instruments. It was not an exclusively occidental affair.

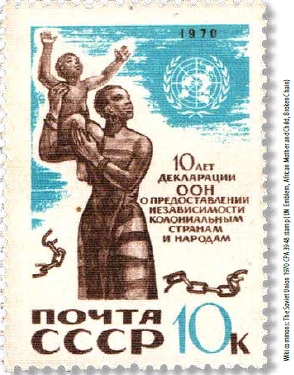

As a matter of fact, the decolonization process after the Second World War was a dramatic process of political emancipation of many countries of a very short lapse of time. Spurred on by the will of Western countries to provide for an upbeat postwar outlook through grand narratives such as Human Rights, the colonies had found a supporting ideology to leverage on for independence. It was indeed a progressive and emancipatory concept. Human Rights became one of the pillars of anti-colonialism and it was therefore untenable that European powers would hold on to their colonial assets. Many leaders of post-colonial African and Asian countries swore by the Human Rights Principles.

However, whether the new sovereign states remained committed to Human Rights principles is highly debatable. Was Human Rights part of the new political projects or simply instrumentalized as a sporadic strategy by those fighting for independence and those who would later mastermind neocolonialist schemes to control former colonies? It has been argued that the leaders of post-colonial states had an ambivalent relation to Human Rights. The principles were used when it accommodated their views. Human rights were especially useful at supranational levels where former colonies would invoke former colonial masters truly respect of Human Rights Principles.

Moreover, what can be felt today is a state of tension between sovereignty of states and Human Rights. Sovereignty refers to the powers of a state to act supremely within the boundaries of its territory. On the other hand, Human Rights seem to place limits on how a state can treat its own citizens. Therefore, it appears that sovereignty and Human Rights are mutually exclusive. This view grossly downplays the role that Human Rights have had in the constitution of these same sovereign states. Indeed, state should be viewed as guarantors of Human Rights. Interestingly the above view that states should be the guarantor of Human Rights has become a pretext for Western powers to interfere in the affairs of former colonies. Interventions of this kind encompassed military actions, economic sanctions and political backing of pro-western politicians. This defeats the idea of self-determination that is connected to Human Rights.

Clearly, the relationship between Human Rights and Decolonization is not straightforward. It has even been argued by some scholars that we should not overlook the colonial origins of the Human Rights concept. It belies the presence of Western ideologies in postcolonial societies. It is further argued that true decolonization would refer to the undoing of colonial socioeconomic arrangements of which rampant capitalism – one of the key driving forces behind colonialism.

To start with, a real and effective Human Rights should advocate for a redistribution of resources and common goods and environmental justice amongst others. A second course of action could consider the hegemony of the State that is enshrined in Western ideology. Indeed, States at times ignore the pluralistic nature of humans and promote uniform cultural practices and traits that negate the rights of people. Lastly, the human is central to the idea of Human Rights. This form of Humanism excludes non-human actors (such as animals and the biodiversity) and following this logic, they have no rights.

To conclude, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was a step in the right direction. However, it left many openings for further improvement and to include the rights of those who have been ignored. This may be why the Declaration of Human Rights has been taxed of cultural relativism. It has been viewed as a grand narrative directed by the West to cling on to its sliding hegemony over the rest of the world. However, it would be more positive to view the openings left for further enhancement to the Declaration of Human Rights as an opportunity for a better world. Interestingly, the Declaration of Human Rights is not the first set of principles that have been elaborated to preserve and promote human dignity. We could consider the Hindu concept of Dharma and the Islamic concept of Umma to this effect. Dharma includes the idea of the individual being part of a whole, the cosmos. As such, entities such as nature has rights; this cannot be found in the Western discourse of Human Rights. Similarly, the Umma speaks of social solidarity which have not been captured by Human Rights. Therefore, there is still work to be done by Human Rights activists to achieve a truly complete Human Rights charter.

Author

AJAY LACHHMAN ( Human Rights Activist)

Dr AVINASH Oojorah ( Scholar )

References

Barreto, J. M. (2014). Epistemologies of the South and human rights: Santos and the quest for global and cognitive justice. Ind. J. Global Legal Stud., 21, 395.

Eckel, J. (2010). Human rights and decolonization: new perspectives and open questions. Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 1(1), 111-135.

Reus-Smit, C. (2001). Human rights and the social construction of sovereignty. Review of international studies, 27(4), 519-538.